The PIP cuts and public opinion

Exempting current claimants will avoid the worst controversies - but there's a chance of more resistance as the cuts are implemented

Sorry for the break in blogging - a combination of having to work flat out on an impending Resolution Foundation report on disability and employers (to be published in mid/late July; more on that soon), and some other reasons to pause (which I’ll come back to). But there’s obviously lots to write about - starting with some reflections on the politics of disability benefit reforms.

In the face of the proposed severe cuts in disability benefits in the UK, are last week’s concessions by the Government enough?

That’s the question that everyone is asking today - and it’s one that I’m not going to directly answer (sorry!), as other people are better-placed to answer it. Instead, I want to point out a few things about public opinion on disability benefit cuts, in the hope that these are useful for thinking this through, not just today and but more broadly for reflecting on the future of Personal Independence Payment (PIP).

Reassessing existing claimants is always unpopular

The Government’s main concession is to exempt existing claimants from the stricter PIP criteria, so that the cut will only be felt by new claimants. Put simply, giving money to people and then taking it away is one of the worst things the benefits system can do. As I said in last year’s report After the WCA, “There is no point in building a benefits system to tackle insecurity and hardship, only for the system to itself create insecurity and hardship day-by-day” by taking benefits away.

Because it is so deeply felt, and because it looks unfair to many people, it is usually taking money away from existing claimants that generates the worst headlines. This is true even when a reform actually results in spending more money - as we saw when PIP was introduced, and people lost their Motability cars.1 And when we look internationally, on the rare occasions that countries are reassessing current disability claimants, we similarly see a lot of public opposition:

In the USA from the late 1970s, there was an attempt to reassess all disability insurance claimants against stricter criteria. This led to drops in claims, followed by a backlash in both the courts and in Congress - leading to certain more lenient rules that are still in force today.2

In the Netherlands in 2004-9, there was a reassessment of incapacity benefit claimants against stricter criteria. There was a significant amount of public opposition, and a new cabinet in 2007 reversed this for those aged 44+ (so that 25,000 people had two reassessments), but for younger claimants the reassessment was fully implemented.3

In Sweden in late 2009, ahead of time limits being introduced on sickness benefits, there were many media stories about e.g. people with cancer that were about to be affected by the reforms. While the reforms were maintained, they were softened and had exemptions added at the last minute in response.4

It’s therefore more common for people to do incapacity/disability benefit cuts only for new claimants, rather than trying to reassess people currently receiving benefits. Indeed, I was talking to one international expert last year, who noted how unusual the UK is in repeatedly trying to do reforms that affect current claimants.

But even cuts for new claimants run the risk of being unpopular in the long run

But while exempting existing claimants from the cuts will avoid some negative headlines, in the long run this will obviously lead to income losses and poverty for many new claimants - and there is still a risk of public disquiet. Before we explain this, we need to dive into public attitudes to disability benefits in a bit more detail.

Firstly, while attitudes have shifted a bit, people are still overwhelmingly supportive of health/disability-related benefits.

The Telegraph had a headline this week that ‘Majority of Britons believe disability-related benefits are too high’ - but this headline is simply wrong, even compared to the text of the article that follows it. A slender majority of Britons now don’t think disability-related benefits should be increased - but only a small minority (11%) think they should be cut. (This all comes from just-released data from the British Social Attitudes survey for 2024).

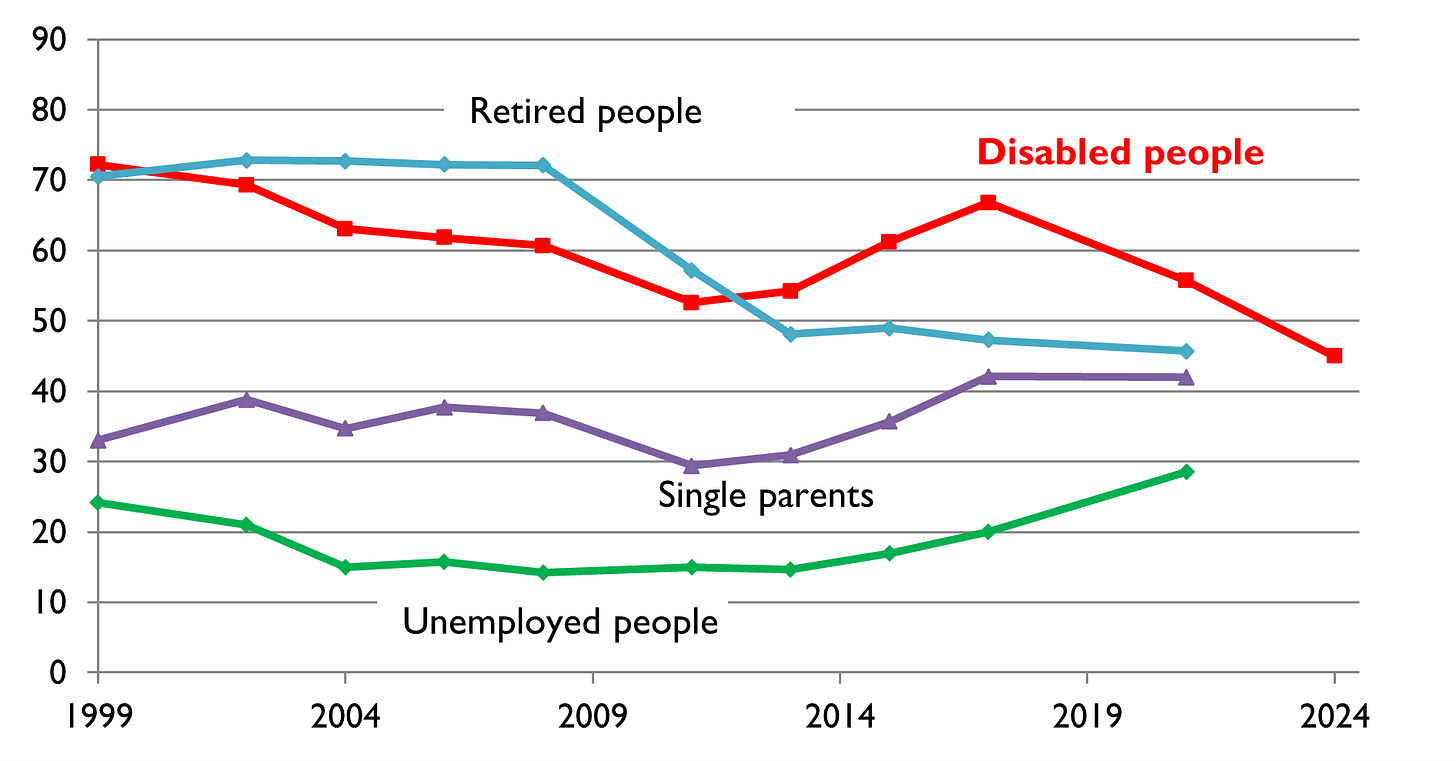

That said, public support for disability benefits has gone down over time. The published BSA data focuses only on disability benefit spending, so I’ve put this alongside support for other types of spending below. Note that in 2024, they only asked about disability benefits - my guess is that asking the question in a very slightly different way will have nudged the figures down slightly.5

Chart 1: Support for more spending on different types of benefit claimants (from the British Social Attitudes survey)

Putting this all together: while support has gone down sharply, people are still pretty supportive of more spending on disability benefits, and very few think there should be less spending.

Secondly, public attitudes are likely to get more opposed to the cuts as they are implemented, rather than less

It’s not sensible to talk about ‘public attitudes to disability benefit claimants’ as a whole.

There are many people who support higher benefits for ‘genuinely disabled’ claimants, but greater strictness for those who are not ‘genuine’.6 For example, from some research of mine, we clearly see that pen portraits of wheelchair users are (on average) seen as much more deserving of state support than people showing symptoms of depression:7

Chart 2: Perceived deservingness of a hypothetical disability benefit claimant (0-10 scale, from Geiger 2021)

Public attitudes, then, are partly about who they think is going to be affected. The BSA question asks about “Benefits for disabled people who cannot work”, so this perhaps largely reflects attitudes to ‘deserving’ or ‘genuine’ disabled people (although it’s not that far away from a YouGov question that asks about ‘people who have a disability’ in general). But there is other evidence that the public are either sympathetic to most claimants, or have ambivalent attitudes:

The BSA survey also shows that only 29% think that it is too easy to claim disability benefits, while 29% think that it is too difficult.

YouGov released some polling last week showing that 46% believe that a clear majority (or more) of disability and sickness benefit claimants are ‘genuinely in need of the assistance’ - 28% thought ‘around half’, and only 14% thought a minority were genuinely in need (the rest didn’t know). YouGov’s related welfare tracker shows a similar picture, but also that this has been hardening over time. Not specifically connected to disability, another YouGov question shows a huge rise in people thinking that welfare in general ‘is not strict enough and is too open to abuse and fraud’.

This ambivalence is longstanding - when I did some more detailed polling a few years ago, I found that substantial minorities thought that some people they knew were not ‘genuine’ claimants, but they also knew people they felt were genuine that had struggled to claim.

(There’s also a lot of push polls flying around, as there always is, but these are less helpful8).

So how will this all change if these cuts are implemented? One possibility is that the PIP cuts will solidify harsher public attitudes to the sorts of people affected - as I’ve explained elsewhere, hostile media/political rhetoric probably gets people to judge the disabled claimants around them as being less genuine. This is primarily for people with ambiguous outward signs of disability (often the case for e.g. fluctuating depression, back pain), and for people that you don’t know very well (e.g. neighbours, distant family) - in the face of little knowledge about someone, people’s judgements are largely determined by their preconceptions. This was many British disabled people’s experience of benefits reform in the 2010s, and there’s some reports of this in e.g. Sweden too after disability benefit cuts.

But my guess is that there will be a backlash when the reality of the cuts bites - in nearly all countries, politicians will justify disability benefit cuts by saying that ‘genuinely disabled’ people won’t be affected. But this is easy to say in advance, and usually is less convincing when people see the reality of who is affected, leading to greater public opposition just after cuts are implemented (which we also saw in the UK in the 2010s). So a policy that looks relatively uncontroversial to the uninformed observer initially may become a public disaster over time, just like the WCA did.

In the case of the PIP cuts, the rhetoric has largely been around cutting benefits for young people with mental health problems - but the reality is that most people affected are 50+ and (in particular) with physical health conditions, as campaigners have been pointing out. And the PIP cuts haven’t come alongside reforms to ensure that the basic rate of benefit is live-able for most people (or to fix social care, or accessible transport, or accessible housing…) - some people are likely to be left without enough money to live on. So whatever public opinion currently is, it’s likely to get more opposed to the government’s reforms as they are implemented.

What do we take from all of this?

Predicting public attitudes - indeed, predicting anything - is a fool’s errand. But given that decisions need to be made, this is what I take from this research:

Exempting people currently receiving benefits will avoid the considerable hardship and distress of taking money away from people, and avoid considerable public opposition.

Public attitudes are ambivalent over the situation for new claimants - but there is a risk of high and rising public opposition when the cuts to new claimants start to bite.

Finally, though, I want to emphasise that these cuts will have huge implications for real people’s lives, not just for politics. Today’s post has been political attitudes, but I will return later in the year to how all of this affects people with health conditions and disabilities themselves, both in terms of their income and their experiences of claiming more broadly. And before then, I’ll return in the next post to think a bit more about what a better PIP assessment might look like.

[PS: If you spot another useful poll, let me know and I’ll keep the post updated, noting any changes I make]

It’s worth adding that PIP was intended to be a cut compared to DLA, which it replace - but in practice, working-age disability benefit (PIP+DLA) spending went up much faster after PIP was introduced. As I discuss here, the reasons for this are complex, but it’s hard to argue that moving from DLA to PIP was actually ‘a cut’ in practice.

See e.g. OECD 2008 and Burkhauser et al 2014.

See e.g. der Burg & Prins 2010 and Tummers et al 2009. See also Kurzer 2013 on the extent to which anti-migrant rhetoric was used to get support for disability benefit reforms.

See e.g. Stendahl 2011 and Ståhl et al 2012.

This is because of question context effects - if you ask people about unemployment benefits (the least popular type) first, and then ask about disability benefits, people are more likely to go ‘oh, I support disability benefits more than unemployment benefits, so I should express this in my answer’. If you just ask about disability benefits, then, you get slightly less support. There’s no definitive evidence on this though, it’s just an educated guess.

Given the deluge of hostile coverage from most political parties, you might expect that in 2025 then you would get even less support than in 2024. But the YouGov trackers seem to suggest this isn’t the case.

btw, it’s not that I am recommending that we divide between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ claimants - there’s some members of the public who make this distinction, and others that don’t, and I’m not here saying that either of these are ‘right’. But either way, given that many members of the public make these distinctions, you need to pay attention to it if you want to understand public opinion.

This is based on randomly-varied vignettes describing hypothetical claimants; to find out exactly how I created it, have a look through the linked paper.

By ‘push poll’, I mean a poll with quite skewed wording that is designed to support campaigning activity. For example, an Amnesty International poll asks people if they agree that ‘taking PIP away from those that need it is cruel’ (providing little further detail on exactly what was asked). Disability Rights UK also have some campaigning-related polling showing that “only 27% of the public support the Government’s proposed benefit reforms”, but which is very difficult to follow. Note that Amnesty and DRUK do brilliant work, but these sorts of poll aren’t very useful if you’re trying to really understand what the public think.