The headline disability benefit cuts are £9bn, not £4.7bn

The OBR are assuming that people change their behaviour in response to the cuts - without this, the cuts are nearly twice as deep

There’s been close scrutiny of many parts of the Spring Statement this week - but I want to briefly describe something that has been missed: that the disability benefit cuts are deeper than they seem, because the figures are after accounting for the way that people change their behaviour.

[Clarification 2pm: by ‘change their behaviour’, I’m not talking about people moving into work. This is mostly about PIP assessors and people receiving benefits changing their behaviour wrt the PIP assessment - see below]

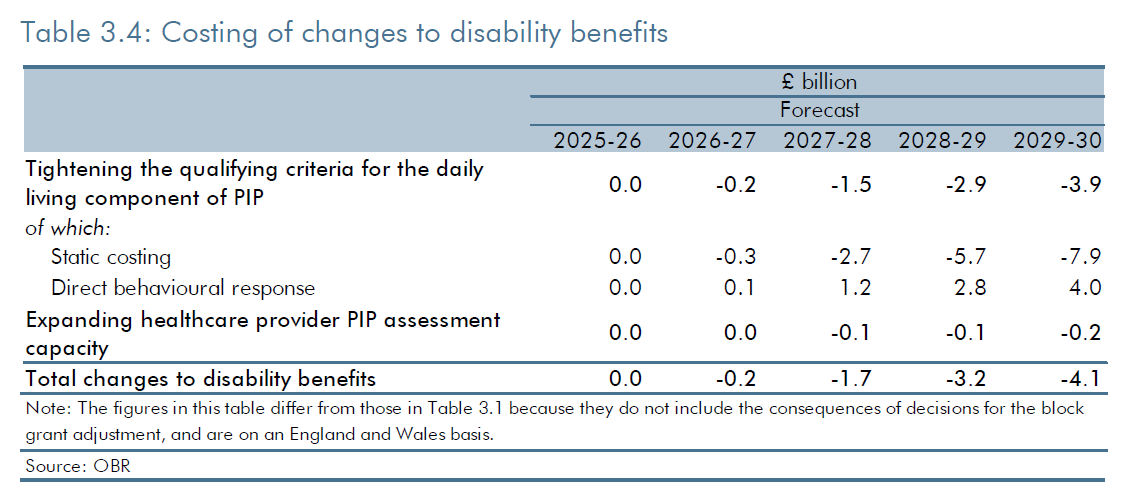

By ‘disability benefit cuts’, I’m talking about PIP (Personal Independence Payment). The detail of what’s going on here is in Table 3.4 of the OBR report, reproduced below:1

The ‘static costing’ is what would happen if you just applied the PIP tightening to the existing caseload - you would see savings of £7.9bn.

OBR say that this would reduce the numbers receiving the PIP daily living component by 1.5 million people (32%). They also say that it would affect more than half of people going through a PIP assessment.2

But the final figure of a smaller - but still significant - £4.1bn cut (in England & Wales),3 and 800,000 people losing the PIP disability living component, is because it takes account of ‘direct behavioural response’.4 The OBR explain (§3.25) this through:

Individuals trying harder to meet the higher threshold - or as they put it, “the strong financial incentive to qualify for the daily living component… and to therefore demonstrate four points in at least one descriptor at assessment”;

The subjectivity of the PIP assessment, both in terms of claimants’ self-reports of their functioning, and assessors’ interpretation of the criteria;

Individuals challenging the system more through mandatory reconsiderations and appeals.

Now, I’m not criticising the OBR here - they’re probably right that changing the PIP criteria will have knock-on effects, and it’s sensible to try to take account of this in financial forecasts. But…

Why the headlines should report the higher figure

Put bluntly, I think the headlines about PIP cuts should talk about £7.9bn or even £9.1bn5 of cuts to PIP, not £4.7bn. There’s three reasons for this: clarity, transparency, and consistency.

Firstly, for clarity. To explain this, let’s use the Treasury’s favourite analogy of a Saturday job. Let’s say I get a £100 bonus for doing overtime, but my employer then cuts it to £50 - obviously a 50% reduction. In this imagined world, the result of this change is that more shifts become classified as ‘overtime’ - partly because managers are trying to soften the blow, and partly because staff morale slips and so people don’t turn up as often for their scheduled shifts, and people are paid overtime when they cover.6 As a result, the employer only saves 25% on their overtime payments.

In this case, does it make sense to describe the cut in the overtime pay as 25% or 50%? For me, it’s a 50% cut from the perspective of the worker, irrespective of how much the employer ultimately saves or how much the worker ultimately has in their pocket.

Secondly, for consistency - when the media talks about cuts, it’s usually talking about the amount that would be saved based on a static change, rather than taking into account behavioural responses.

If we go back to the largest welfare cut in recent years, the 2015 summer budget, the OBR doesn’t seem to score behavioural responses at all. This is despite the OBR later accepting that the change to ESA WRAG may have led to behavioural responses that diluted the cuts.7 Indeed I would go further, and argue that the significant cuts to welfare in the 2010s are a clear contributing factor to the rise in PIP claims, a behavioural response that (inadvertently) diluted the proposed cuts.

Nor were any behavioural responses scored by the OBR last time there was a change to PIP (later abandoned), in the 2016 Budget.8

A caveat here: the OBR are trying to score more behaviorual responses to welfare policies, in a bid to do better forecasts - which is to their credit. So the Conservatives’ planned cut to incapacity benefits via the WCA did include the effects of behavioural responses: this is a static £2.7bn cut (in 2029-30), but only a £1.6bn cut after taking behavioural responses into account. Even here, though, none of this was clear at the time - we were in the dark about the extent of this until this week’s spreadsheets were released.9

Finally, for transparency - it’s completely reasonable to talk about the impacts of cuts after accounting for behavioural effects, but I just think that most people haven’t realised what’s going on, despite footnotes that say ‘accounting for behavioural effects’. Moreover, the estimates of behavioural effects are incredibly uncertain (as the OBR explicitly flag). My guess is that the OBR’s estimates of behavioural effects are too high,10 and as a result, that the cuts even after accounting for behavioural effects are bigger than £4.7bn. But either way, at this stage where no-one really knows, drawing attention to this assumption is really crucial.

Seeing the cuts as accurately as possible

It’s great that there is so much information now available to scrutinise these proposed changes - from the OBR, and the Treasury’s distributional analysis, and the DWP’s impact assessment. And it’s very difficult to summarise changes in spending in a single figure.

But I do think that it’s helpful to uncover this assumption more clearly - to talk about £9bn of cuts on paper, which depending on how claimants react, may lead to £5bn of spending savings overall.

Similarly, echoing others, I think it’s helpful to flag the reversal of the never-implemented £1.6bn WCA cut and whether this should be counted as ‘spending’ (as Iain Porter and Tom Pollard have noted), and the fact that the employment impacts from most of these changes haven’t been taken into account yet (as Tom Clark notes). All of these things are critically important.

Numbers can conceal as much as they reveal, but I think MPs and others are capable of dealing with a few different numbers here - where assumptions are crucial, we want to bring these to light, rather than hiding them behind a single number.

Apologies that this is a screenshot, I was doing this to clearly show it was from the OBR report - if you need the original table for accessibility reasons, see Table 3.4 of the OBR’s Excel tables. The main text also explains the table in words.

The OBR say (§3.24), “58 per cent of onflows and 52 per cent of award reviews among the existing stock of claimants qualify for the daily living component without scoring four points or more in any descriptor.”

Note that the breakdowns are for England & Wales only, which is why the total saving of £4.1bn in this table is lower than the £4.7bn that this is estimated to save for the UK in total.

As you can see in the table, there is also £0.2bn of spending on expanding healthcare provider PIP assessment capacity, so the policy change ultimately costs £4.1bn rather than £3.9bn. But in the rest of this piece, I’ll ignore this.

The £9.1bn is a crude calculation to extend the static costing of the PIP reform to the whole of the UK, as the £7.9bn cut only applies to England & Wales. (The OBR’s estimate for the UK-wide PIP change is £4.7bn, vs. £4.1bn for just England & Wales - so a crude estimate of the UK-wide cut is 7.9*4.7/4.1, which is £9.1bn).

Sorry if this is a terrible analogy, or an unrealistic scenario - the perils of trying to write blogs quickly, because coming up with good analogies is really hard… Let me know if you think of a better one!

You can see this in the OBR’s October 2024 Welfare Trends Report (§3.18-3.19 - full disclaimer, they mention that I was one of the people who thought that this is what happened!). They note the significant uncertainties here, but conclude, the evidence “is consistent with the higher award approval rates [for ESA Support Group] eventually rising after the policy change [to cut the rate for ESA WRAG], although it is not possible to fully isolate policy effects from wider changes in claimants’ conditions.”

See Table 4.24 and §of the OBR’s March 2016 report. They don’t spend much time explaining this forecast, and there’s no mention of behavioural responses - the text just mentions a £1.3bn saving at the end of the forecast (which is actually hard to see in any OBR tables; it’s clearer in the Budget Red Book p215).

Table 3.2 of the March 2025 OBR report shows the ‘direct behavioural response’ figures for the reversal of the 2023 WCA reforms. However, at the time of the 2023 WCA reforms, these don’t seem to be mentioned at all in the OBR’s materials (not in Table 3.5 that shows the costings, nor the Table 3.4 that shows the caseload impacts, nor in the two follow-ups about the WCA change’s impacts). The behavioural response is mentioned in the text of the OBR’s November 2023 report (§3.24), but no numbers were put against this.

The scale of the behavioural effects is really high - 36% of the total cut in 2026-27, rising to 50% in 2029-30. This is noticeably higher than the assumed behavioural effect for the (now-cancelled) WCA cut, which was 29% in the first year rising to 40% in 2029-30. I also think that the jump between 2 points and 4 points in the PIP mobility descriptors is larger than the threshold in other disability assessments (though this is just my personal opinion, and clearly all such disability assessments do have an element of subjectivity in them).

Hi Ben. Great post as always - and I agree that the headline figure when it is framed in terms of cuts that will be endured should be one that doesn't assume (inherently very uncertain) behavioural responses.

I think that also feeds in the analogy question (and I agree that analogies are very helpful but also very hard to get right!). Your analogy is written from the perspective of the worker, who is getting a 50% cut to their overtime pay. But (in this analogy) the OBR are more like the employer's accountant - they they are trying to tell the employer how much money they would SAVE by cutting overtime pay. In order to give the employer the best estimate of this, they are trying to account for the behavioural impact this cut would have. From their perspective, they shouldn't just say "you will save 50% on your overtime payments" because, given likely behavioural effects, that is almost certainly not true. Instead it's more accurate for them to say "you'll probably save about 25%".

From the perspective of a journalist, maybe the best thing to do is not to concentrate on what will be 'saved' at all (since that is inherently uncertain) - but instead focus on the specific things that are happening in terms of policy - i.e. what are the exact cuts to PiP/changes to thresholds and how will they affect people. For disabled people the headline figure of how much the government may or may not save is not that relevant after all.