How job quality has changed since Covid

The highest-quality survey series is finally out, telling us how jobs have really changed since 2017

The highest-quality survey on the changing nature of work in Britain was released last week - so in the interests of telling you about this ASAP, I’ve put other posts on the backburner (including follow-ups to my last two posts, sorry…).

The new data comes from the Skills and Employment Survey, which asks a representative sample of the British workforce to describe their current job. It’s an amazing resource - it’s been done periodically in 1992, 1997, 2001, 2006, 2012, 2017 using consistent methods, and it’s both more detailed and more trustworthy than any other survey. It therefore features heavily in things like the Resolution Foundation’s Economy 2030 inquiry, and recent work by the TUC, ippr et al.

And now we have data for 2024!

How work has got better

[Quick note: Rather than a single summary report, the SES team have written 8 short reports on different things - I’ve picked out the key trends from across these reports. In the interests of getting this to you quickly, I’m screenshotting the charts - but if you follow the links, you can get the underlying data]

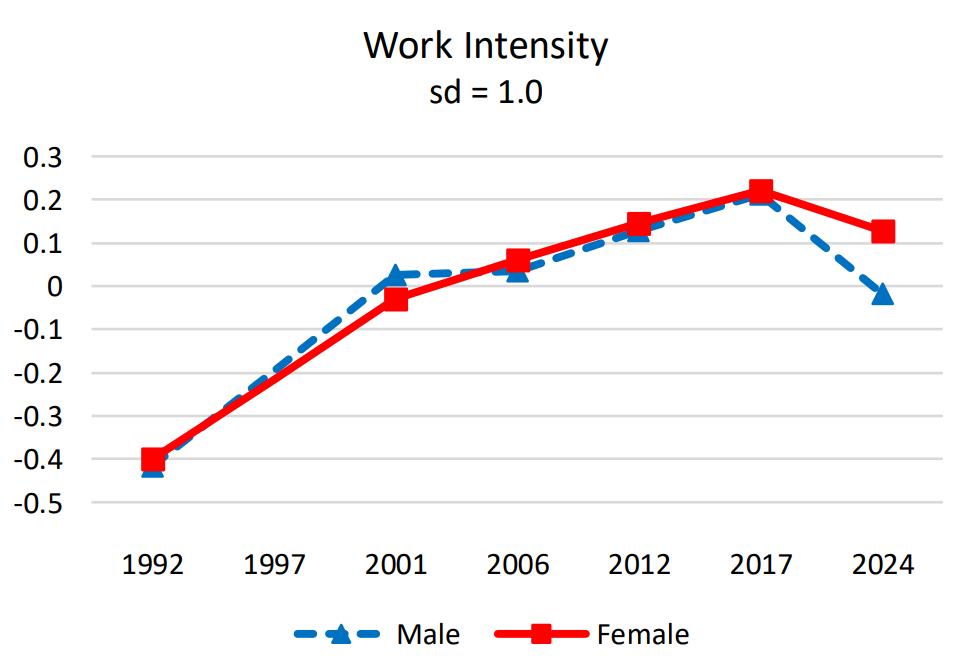

Firstly, the good news - job intensity1 has fallen since 2017, as shown in the chart below. This fall takes women back to the level of job intensity in 2012, and men back to the level of job intensity in 2001 - but note that the average intensity of work is still much higher than it was 1992. This recent fall in intensity is a bit of a surprise2, but I don’t want to make any snap judgements about why this happened - for the time being, let’s just get our head around how work has changed.

There’s also a rise in ‘Working Time Quality’, particularly for men (see chart below) - this is a mix of not having to work long hours, and being able to choose the start/finish times of work.3 Separately, there’s obviously been a sharp rise in home working. This is in line with what we’d expect since Covid.

How work has got worse

But that’s where the good news ends. Control over the way that you do your job (‘task discretion’) has fallen to new lows.4 Control over the way you do your job at the team level (‘semi-autonomous teamwork’) has also fallen sharply since 2017:5

This is particularly surprising because task discretion is closely linked to skill levels, and skill levels have increased.6 The SES team break the recent trend down by skill, finding that declining discretion can be seen in both high-skilled and low-skilled workers (though not in-betweeen; see chart below).7 More detailed analyses find that the declines in task discretion are particularly strong among ‘associate professionals and among caring and sales personnel.’

The picture on organisational participation is more mixed - compared to 2017, workers are more likely to say that there were consultative meetings, but less likely to say that they had any real influence…

How trustworthy is the data?

Finally, it’s worth flagging that the trends need to be caveated slightly. This is undoubtedly the most trustworthy comparison of job quality trends that there is. At the same time, EVERY survey series is facing the same issue: the sharp decline in response rates over time.

In the case of SES, the response rate has dropped sharply - from 49.5% in 2017 to 32.1% in 2024. This creates a risk of increased bias, alongside a further slight risk because of a small change in the way that people were selected to take part.8 It also continues a drop in response rates across each wave of the SES series, from 71.5-66.2-61.7-48.7-49.5-32.1% across 1992-2001-2006-2012-2017-2024.9

Still, given the high-quality nature of the study (ranging from data collection to weighting), this is still the best data available on the changing nature of work, and can be considered alongside other sources to get even more confidence in drawing a picture of what’s happened. So it’s the raw material for trying to understand what’s been going on, what’s been driving it, and what can be done going forward - all of which I’ll come back to later in the year.

The SES team say, “‘Work Intensity’ is defined as the rate of physical and/or mental input to work tasks performed during the working day. It depends mainly on workload and the time available to get things done. Our Work Intensity index combines three indicators in one standardised index, consistent over time, covering the pace of work, the pressure of deadlines, and the perception of required hard work.”

My favourite political commentator, Stephen Bush, happened to speculate on this just before the SES 2024 launch. His hunch was that as minimum wage rises in the 2010s hadn’t led to productivity increases, they’d instead led to rising intensification of work in lower-paid jobs (which in turn might explain rising sickness absence). SES shows that intensification hasn’t happened, though equally, Stephen might be correct if we replace ‘job intensification’ with ‘other ways in which work got worse’, as we’ll see.

The SES team say, “The Working Time Quality index we use is a composite index (having an average of zero, positive scores mean above average, negative numbers below average). It combines an indicator of employee control over the start and finish times of work, which evidence confirms is positively associated with wellbeing, with an indicator for normally working fewer than 48 hours per week, since working longer hours has detrimental health effects. The composite index is standardised, so that positive scores mean above average working time quality, and conversely for negative numbers.”

I’ve edited this chart slightly, to (i) to join the dot from 1992 to 2001 for semi-autonomous teamwork; and (ii) remove ‘teamwork’, as discussed in the text. As you’ll see in the source report, teamwork has gone up, particularly 2001-2006 (from 43 to 57%), then rose slightly at each survey wave to 63% in 2024.

Re the measures, the SES team say: “The survey included four questions which assess how much task discretion or personal influence people had over specific aspects of their job tasks: • How hard they work. • Deciding what tasks they are to do. • How the tasks are done. • The quality standards to which they work. The response options were ‘a great deal’, ‘a fair amount’, ‘not much’ and ‘not much at all’. A summary index was constructed by reversing the scoring (so that high scores indicate high discretion) and taking the average of the responses to the four items… a score of 4 indicated ‘high discretion’ with an average response of ‘a great deal’ across the four items.

The SES team say, “For all surveys other than 1997, employees were initially asked whether they usually worked on their own or together as a group with one or more other employees in a similar position to their own, providing an overall measure of teamwork. Those who did work in a team were then asked about the influence the team exercised over the same four aspects of work used in the measure of task discretion. An average influence score was created and teams that had a score equivalent to ‘a great deal’ or ‘a fair amount’ of influence are taken as involving semi-autonomous teamwork.”

In a different report, the SES team find that a combined measure of autonomy/skill has risen since 2017. This presumably means that skills - measured in that index as a job’s skill requirements and level of complexity - have increased. There’s a further report that goes into skills in detail, which basically shows increases in computer and literacy skills, plus a sharp rise in requiring a degree alongside a slight decline in being overqualified, but with some other things more mixed (e.g. training has gone up, but a need for training to do the job has not).

The broad groups are created as follows: “This can be seen in Figure 3 which broadly categorises occupations into a more highly skilled group of professionals, managers, and associate professionals; an intermediate group of administrative, skilled manual and personal service workers; and a lower skilled group of sales, operatives and elementary workers.”

In past waves, one person in each household was randomly selected to take part - in 2024, every person in the household was invited to take part (this was a way of boosting the size of the sample). So the household-level response rate in 2024 is 39.8% (compared to a response rate of 32.1% among individual people who were eligible to take part). This perhaps slightly changes the possible biases in the sample, though I’d guess that this is a small change.

I’ve assembled these response rates from the various technical reports accompanying the studies - it’s not given anywhere by the SES team. As a result, there’s a chance that their ways of calculating response rates aren’t fully consistent between waves - particularly in 1992.