Conditionality and mental health: new evidence

A new study of Danish RCTs shows how the impact of conditionality depends on people's pre-existing mental health

While there’s a lot of strong opinions about whether threatening claimants with sanctions (‘conditionality’) has positive or negative impacts, the evidence is often pretty weak – particularly when it comes to longer-term impacts, and particularly the impacts for people with mental health problems.1

So I was really excited to see a new paper led by Martin Bækgaard (who has led an amazing project on administrative burden that I’ll be coming back to). This uses major randomised experiments in Denmark to provide some important new evidence – not just on the overall effects on conditionality, but crucially on how these effects are different for different people.

Put simply, there’s now good enough evidence to be pretty sure that conditionality has much worse impacts on people that have pre-existing mental health problems. In this post, I summarise what the paper did and what it found - and what this means for the upcoming DWP green paper on health & disability.

‘Gold-standard evidence’?

Just to be clear: I’m not saying that experiments provide ‘gold standard evidence’. It’s easy to over-claim the importance of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for policymaking.2 Still, good policy experiments can be really useful for shedding light on the average impacts of a policy in a particular group, particularly when there are multiple ways in which the policy affects people, some positive and others negative. Good qualitative research is excellent at drawing out these mechanisms - we’ve got loads of great qualitative studies about the problems of conditionality for people with health problems - but can’t say much about the average effect across these opposing mechanisms.3 So this is new study is really important.

The study is just published in the journal PNAS4, and focuses on 5 RCTs in Denmark from 2005-8. Mostly they focus on the biggest two trials though: one looking at new unemployment insurance claimants (Unemp trial #1), and the other looking at social assistance claimants who’ve been unemployed 6mths+ (SocAss trial). In both cases, the experiments randomly allocated some claimants to receive a greater amount of early and frequent individual meetings, with meetings at least every fortnight rather than every 3mths (Unemp trial #1 also combines this with a 2wk jobsearch assistance programme after 5-6wks and an extra activation programme after 4mths rather than 12mths).5 So this is testing the combined effect of conditionality and early activation.

The quality of this study is pretty strong. It uses administrative data to cover both work/benefits outcomes and mental health outcomes, and to look at long-term (5-10 year) effects. I have two minor quibbles: (1) the study isn’t preregistered so there’s a chance that the authors unconsciously chose their outcomes where the story was strongest;6 and (2) they use some pretty complicated statistics that I think are largely unnecessary7; so we have to trust the authors a bit more than we should. And frustratingly, despite all the fancy stats, their use of statistical significance could be better, so their claims need to be caveated a little.8 But basically this is a strong study by an excellent team, which is higher-quality than most of the wider literature.

The complex effects of conditionality

This is a story that unfolds in two parts. Firstly, we can see the average effects of the two main trials for four main outcomes, which is shown in Figure 1 below (repeated from the paper). This shows a pretty clear message:

A positive effect of conditionality on earnings (and perhaps also benefit non-receipt), but only in the unemployment benefits trial';

A negative effect of conditionality on mental health (i.e. more mental health prescriptions, primarily anti-anxiety/antipsychotic meds), but only in the social assistance trial.

Figure 1: Effect of the conditionality trials on four key outcomes

This already is quite striking - but if we divide each trial into people with pre-existing mental health problems or not, then the difference in impacts becomes even clearer. In Figure 1 above, we saw that unemployment trial #1 on average had positive effects on earnings. In Figure 2 just below, we can see that in the long term this is entirely driven by people without initial mental health problems.

Figure 2: Effect of Unemployment trial #1 on earnings, split by initial mental health

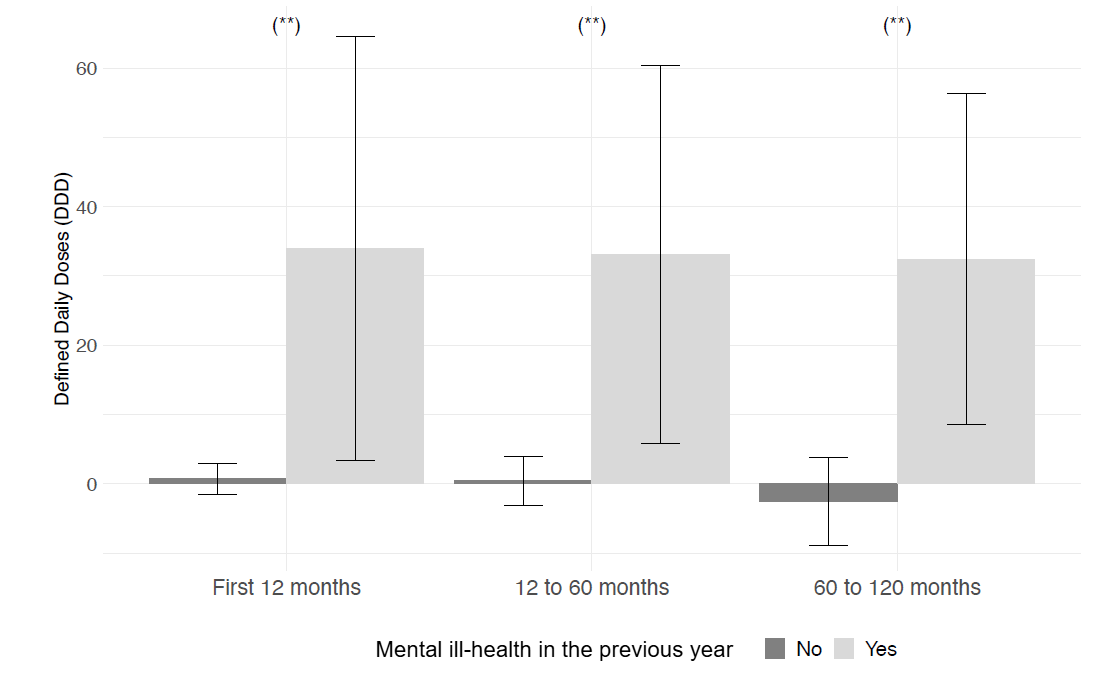

Similarly, in Figure 1 above, we saw that the social assistance trial on average led to greater numbers of anxiety/psychosis-related prescriptions. In Figure 3 just below, we can see in parallel that this is entirely driven by people with initial mental health problems.

Figure 3: Effect of Social Assistance trial #1 on anxiety/psychosis (N05) prescriptions, split by initial mental health

It’s worth flagging that I think the evidence is a little weaker than they claim it to be, for two statistics-related reasons I explain in the footnote.9 Despite these issues, I still I think this is pretty strong evidence overall, and agree with the overall message.

The message to policymakers

The basic message from this study is: the effects of conditionality depend crucially on the group of people that are affected. People without pre-existing health problems were more likely to move into work as a result of these additional early meetings and activation (i.e. extra support). But people with pre-existing mental health problems saw no positive employment effects, and instead saw a rise in anxiety/psychosis-related prescriptions.

This is one of the few studies that shows the mental health impacts of conditionality, split by people’s initial mental health. But it’s consistent with a small wider literature that I reviewed back in 2017, where I concluded that the evidence suggests disabled people will not be helped by conditionality:

Even in countries that do conditionality much better than the UK, conditionality for disabled people is at best ineffective, and at worst actively counterproductive. (The paper also explains why I think Denmark implements conditionality much less badly than the UK).

Indeed, the best evidence we have from the UK (from the National Audit Office, looking at random allocation of claimants to Work Programme providers) found that disabled people that were allocated to high-sanctioning providers were less likely to end up in work.

There’s no more recent reviews unfortunately (I’m adding it to my ‘to-do’ pile…), and not a lot of more recent studies. A more recent UK trial of extra support combined with conditionality for certain ESA WRAG claimants found no effect on work outcomes for people with mental health conditions, but that more of them were pushed out of the benefits system entirely. (This is compared to positive findings for people without mental health conditions). Bastiaans et al 2024 in the Netherlands also found no employment impacts, though in contrast found that men with pre-existing mental health conditions had lower mental health prescriptions 3-4 years later.

Putting all this together, this is how I would summarise it for policymakers:

For people without mental health problems, conditionality can have positive effects on job entry. But there’s also wider evidence that they cause people to be in worse jobs, and that they cause other people to leave benefits without having a job (see my 2017 review).

For people with mental health problems, conditionality is likely to either have no impact on employment or to even push people away from work, and sometimes makes their mental health worse.

These effects also depend on what the policy looks like. ‘Conditionality’ is a word that conceals a huge range of different interventions - some of which are mostly about providing support that people are compelled to take up, and others are about punitive policies that are implemented badly. The evidence suggests that even more supportive forms of conditionality can be counterproductive for people with mental health problems - but the impacts are likely to be even worse for less supportive conditionality.

There’s an obvious question from policymakers here: do we know exactly which people with mental health problems are likely to see harms from conditionality? But as it stands, there’s not much more we can say.

Finally, I spent way, way longer digging into this paper than I expected. This is a really great addition to the literature, so I thought it was simply a matter of explaining what it found - but evidence is complex, and figuring out what’s going on here is tricky. The real world is often not neat enough to easily fit into a 700-word blog post…

I summarise some of the wider literature towards the end of the article.

They have their own flaws, particularly because they can’t be used to answer many crucial questions, and say little on their own about what impact a policy is going to have if it’s adopted in a new time & place. I could write a whole separate series of blog posts about this - but in the meantime, interested readers should check out Deaton & Cartwright 2018 and Cartwright 2007.

I say more about this in this talk (to an audience of philosophers rather than social policy people). I will eventually write this up too…

Annoyingly the publication is not open access - if you’re not based in a university and would like a copy of the full paper, just drop me an email.

It’s worth noting that unemployment insurance at this time has a 4yr limit. You can find out more about the trials and the benefits in the supplementary material ‘SI Trial’. Note that compliance with the interventions is not perfect (e.g. 75% of those in Unemp trial #1 participated in the 2wk jobsearch assistance programme, and 50% of those in the SocAss trial were exempted during at least one period). But the authors correctly include all of these people in the analysis, to avoid biasing the results (i.e. this is an ‘intent-to-treat’ analysis, in the language of evaluators).

The lack of preregistration is a particular problem because they have so many different outcomes - there’s 21 secondary outcomes listed in Table S3 (each of which is observed over three time periods). So for example, it’s a fairly arbitrary choice about whether you’d measure employment outcomes in terms of weeks of employment vs. total earnings (they chose the latter). And particularly for mental health outcomes, even when looking at prescriptions, it’s an arbitrary choice about whether you look at total number of prescriptions vs. the number of people who receive a mental health-related drug (they chose the former), let alone whether to use prescriptions vs. psychiatric diagnoses, GP vists, or medication/healthcare costs. As I’ll return to below, the results are noticeably different when you measure things in a different way, and they didn’t say in advance how they were going to measure anything. For more on preregistration, see Nosek et al 2018 (also in PNAS, like the paper here!) and Lakens 2019 and 2024.

The over-complicated analysis is in terms of how they show that the impacts of the interventions were different in people with vs. without pre-existing mental ill-health. The simplest way of doing this is just to split the sample, and look at the effect in each group, and test whether it’s different. Instead, they estimate ‘causal forest models’ that allow them to estimate a conditional average treatment effect (CATE) for each person in the sample, and then compare the CATEs for people with vs. without pre-existing mental ill-health. They say that this enhances the precision and robustness of estimation, but this comes at the cost of some further assumptions that I’m not clear on (I’ve never used this approach), and more generally at the cost of a lack of being able to explain this simply. I would have much preferred them to show the results of the simple comparison as well as this more sophisticated approach, so that we can see if it makes any difference or not (I would have more confidence in it if it basically shows the same thing as a simpler analysis!).

There’s two statistical problems here. Firstly, they compare subgroup effects (or different effects in the different trials) by looking at whether they are significant in one group vs. the other. This isn’t great - it wrongly inflates the chances of showing a subgroup effect (see Brookes et al 2001, Gelman & Stern 2006 and Bell et al 2014). It’s much better to directly compare the two effects, and see if this contrast is itself statistically significant / look at the confidence interval around the difference.

Secondly, they are looking at a lot of different outcomes, and the more outcomes you look at the more likely you are to find that some of them are significant, even if there’s nothing going on. They have at least 24 primary tests (4 outcomes x 3 time periods x 2 trials), and 126 secondary tests (21 outcomes x 3 time periods 2 time trials). They do some additional tests to look at the ‘Family-Wise Error Rate’ - i.e. to adjust the statistical significance level to account for these multiple tests. But annoyingly, this adjustment is only shown in the supplementary tables though, and not in the main figures in the report (including the ones repeated in the blog post itself).

These are pretty common statistical problems in the wider literature - but it’s strange that they did these, given that in many respects their statistical knowledge is much greater than mine! I’ll try to come back to the problems in established statistical practice at some point.

Firstly, as I said in the earlier footnotes, the authors don’t directly compare the effects in the two groups, they just say ‘this has a significant effect in one group, but basically no effect in the other’. From what I can tell, the differences in Figure 2 (for employment effects in Unemp Trial #1) are not significant, but the differences in Figure 3 (for mental health effects in the Social Assistance Trial) are.

Secondly, they find no effects of the Social Assistance Trial on the proportion of people who have mental health-related prescriptions - they only find an impact on the number of prescriptions per se. So this isn’t making more people have mental health problems - instead, it’s making the mental health worse among those with pre-existing problems. This is an interesting finding, but it’s not clear to me why you would choose number of prescriptions as your primary outcome, which goes back to the point above about having a lot of different outcomes flying about.