On the OBR's new Welfare Trends Report

It repeatedly makes the problems seem worse than they are - but it's a valuable resource nevertheless

This is a rapid response to the OBR’s just-released Welfare Trends Report - which is particularly relevant to this blog this year because it focuses on incapacity benefits.

The report is a fantastic resource with a wealth of new data and analysis, as we would expect from the brilliant OBR team (which often gets hold of data that are otherwise hidden). It also provides a really clear explanation of the last 40 years of incapacity benefits policy, of which there are very few.

But nevertheless, I think that it frames the issues in several ways that are potentially misleading, and make the problems with incapacity benefits spending seem larger than they really are. In this blog post, I try to quickly explain what these are, and how these change the overall story of what’s been going on.

[To be transparent: the OBR kindly chatted to me in the course of doing the report (as they declare in the Foreword), so this echoes some points that I have made to them directly.]

Making caseload rises seem bigger

The cut to benefit rates for less severely disabled claimants

The first problem is the way that the OBR deal with the 2017 cut in benefit rates for what they term ‘less severely disabled claimants’. This change meant that new claimants who are placed into the ESA WRAG or UC LCW1 groups by the WCA don’t receive any more money than if they were simply unemployed (although they do face less stringent conditionality). The OBR and DWP classify these people as ‘incapacity benefit claimants’,2 but this is puzzling - if they get no more money than unemployment benefit claimants, then surely it’s better to think of them as unemployment benefit claimants?

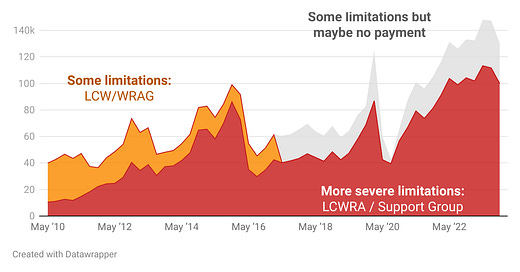

This makes a big difference to the story. The OBR do mention this in several places, but they largely don’t make it clear in their charts.3 But we can re-draw their charts to make this clearer. For example, my chart below shows the trend in incapacity benefit on-flows, but making it much clearer that some of the rise in claims is due to people that probably don’t receive any payments.

It’s clear that incapacity benefits have risen since Covid - but by much less than they appear to if the ‘no payment’ incapacity group is included. Indeed, on-flows now are only a small amount higher than the on-flows in late 2015. (It’s also worth noting that the sharp rise in on-flows happens just before Covid, surprisingly).

It’s misleading to start trends from 2010

Much of the OBR’s analysis shows how incapacity benefit claims have changed since 2010, which is when ESA properly started. For example, they show that on-flows have tripled from 2010-11 to 2022-23.

However, 2010-11 is a really misleading moment to start a trend. This is when the WCA had just been introduced for new claimants, and - let’s pull no punches - it was a complete disaster. I have looked at benefits disability assessments across many countries, and I don’t think there has ever been more outcry about an assessment than in the early years of the WCA. So the early years of the WCA are not a steady state; they’re a time of unsustainable harshness.

It’s therefore no surprise to see that incapacity benefit on-flows rose from 2010-11 to 2014-15 - this was an unavoidable correction to a failing policy. It doesn’t tell us anything useful about the recent period. Instead, it makes much more sense to start from 2014-15, when the WCA had bedded-in (much as it has always fluctuated). If we break down the reasons why incapacity benefit on-flows increased from 2014-15 to 2022-23, the OBR show:4

Increases in initial claims lead to a rise in the incapacity benefits on-flow of 50,000 people per year. (Chart 3.6 fleshes this out usefully).

A falling dropout rate (between the initial claim and the assessment) leads to a rise in the on-flow of 135,000 people per year.

A more generous approval rate at the WCA leads to a rise in the on-flow of 60,000 people per year.

Note: this misleading includes less severely disabled people who receive no extra money as ‘incapacity benefit claimants’, as I explained just above - so the true rise in the on-flow is less than appears.5

Even so: if we exclude the atypical early years of the WCA, we reverse the OBR’s headline conclusion about what explains rising incapacity benefit on-flows. Instead of this being largely the result of rising approval rates, it’s instead the result of falling dropouts (which explains 56% of the rise). The OBR’s discussion of the reasons behind this is really important, and together this is a really valuable contribution - but one that’s slightly undermined by the way this is framed in the report.6

Benefit claims aren’t counted consistently

As I’ve explained repeatedly on this blog, benefit claims are not counted consistently over time in UC vs. legacy benefits. This means that it looks like benefit claims are going up, even if nothing is changing. The OBR do admit this briefly,7 which is great to see, but there’s no mention of this in the charts or the main headlines, e.g. when the executive summary says that the OBR forecast an ‘all-time high’ incapacity benefit claim rate in 2028-29. This probably has a considerable impact in making claims today look bigger than they were in the past.

The pension age has been rising

Now, the OBR do an excellent job of talking about the impact of the rising State Pension Age (see Box 3.1). They explain that (ignoring the pension age rise) there’s two distinct periods here - a fall in the caseload of 330k to 2019/20, and a 670k rise since then. But they also show that the 330,000 rise in the incapacity benefits caseload 2008/9→2023/24 is entirely explained by the rising pension age - and that’s before we account for the issues above!

But the effect of the rising pension age is often lost in the wider report, because none of the graphs actually take account of this - we just see caseloads rising, spending rising, on-flows rising etc. And as I say here, very crudely, we would expect spending to rise by 8% from 2010 simply because of the rising pension age. So even though the report does a consistently good job of drawing attention to this issue, I still think it would be better to take out the effect of the rising pension age completely from all of the graphs (and making sensible guesses where age-disaggregated data aren’t available).

The wider context of welfare spending

As well as the report making the caseload/on-flow rises look bigger, there’s a wider issue about working-age welfare spending as a whole. And I might regret saying this, but the main chart on this in the OBR’s report looks simply wrong.

I’ve previously said this about an OBR chart, and then later had to qualify some of my criticisms. As I said there, “when it comes to things that have already happened, the OBR are probably right…My first lesson: if someone is disagreeing with the OBR, you should probably go with the OBR”. So take this with a pinch of salt while I check it with the OBR. [17:10: this is indeed correct, see note just below].

The OBR try to contextualise the trends in incapacity benefit spending by showing wider working-age benefit spending (Chart 1.3). I strongly encouraged them to do this, because I don’t think you can understand welfare today without understanding that rising health-related spending has come alongside lower welfare spending on other things. So I’m really glad the chart is there.

But I think it’s wrong. It definitely shows a different picture than my recent chart. I’ve tried to reconstruct what they’ve done,8 and I think they’ve made two mistakes, alongside making a different choice to me:

They’ve missed out Tax Credits (and Family Credit), but included Universal Credit. Obviously this makes current spending look a lot higher. This just seems like an error.

They’ve excluded benefits that are nominally for children, like Child Benefit, large chunks of Income Support in the 1990s and 2000s, children’s DLA etc. I think this is misleading, because benefits for kids are not actually given to five-year olds to spend on Pokemon cards - they go to their parents/carers. So it makes sense to look at spending on all non-pensioner benefits, combining benefits for kids and working-age adults together (as I do in my chart), rather than to treat the two-child limit as something that doesn’t affect working-age adults (as the OBR do). This is perhaps not an ‘error’, but it’s still misleading.

They’ve also focused on incapacity benefits spending vs. all other working-age benefits. So sharply rising spending on disability extra cost benefits is in the ‘other’ category. This is just a different way of presenting the data, though I still think my chart is clearer on how this all fits together.

The result of this is that it looks like working-age welfare spending is ‘out of control’ (not their words, but it’s how the graph looks), when that’s just not what’s going on.

I’ll put a note here if the OBR clarify this point further - but I wanted to post a rapid reaction to the OBR report while it’s still current. [Added 17:10: the OBR have confirmed that my guess above is right, and they’ll correct the charts online when they get a chance - it’s great that they responded so quickly and helpfully].

Conclusion: telling a different story

To be clear - the OBR report is essential reading for anyone that works on these issues. There are two things that I understand far better now than I did before, namely (i) the role of falling dropout rates in explaining higher numbers of claims (see §3.11-3.12); and (ii) how off-flows mostly fluctuate in line with the level and harshness of disability re-assessments. They also surprisingly suggest that the introduction of mandatory reconsideration made surprisingly little difference to claim numbers (even if they weren’t a great experience for some claimants).

And perhaps most of all, they are up-front about the many uncertainties that come with forecasting incapacity spending - a corrective to the way that their forecasts are sometimes treated more solidly than they really deserve. I’ll come back to this in future posts, but it’s clear that treating these forecasts as the gospel truth isn’t the OBR’s fault, and their transparency here is great to see.

But still: I feel that in several ways, their framing makes the issues of rising incapacity claims loom larger than it should. Claim rates and on-flows are lower if we define incapacity benefit claimants as people that actually receiving any more money; if we take account of the rising pension age; if we don’t start charts from 2010-11; and if we count benefit claims consistently - so all of these together add up to a different picture. [Added 9:22am: the OBR largely do mention these issues in the report, to their credit, but the impact of these is largely lost in the headlines and charts]. And the wider context of non-pensioner welfare spending isn’t clear at all from the report.

We have probably seen a recent rise in incapacity claims, and the OBR report offers far more insight into why this has been happening than anyone else - but it is not quite the looming crisis that it often appears to be. To repeat again: welfare spending is not ‘out-of-control’…

This is the ESA ‘Work-Related Activity Group’ and the UC ‘Limited Capability for Work’ group, who are best summarised as ‘less severely disabled’ (in the WCA’s classification) than people in the ESA ‘Support Group’ or UC ‘Limited Capability for Work-Related Activity Group’. Existing claimants in these groups do still receive additional payments via transitional protections. See the House of Commons Library briefing on this.

They say, “"An important definitional point is that, since 2017, new claims in the less severe incapacity group no longer receive higher awards relative to unemployment-related claimants and those found fit for work at a work capability assessment. In line with the Department for Work and Pensions’ (DWP’s) approach to classifying health-related claims, and reflecting the fact that they still experience fewer work-search requirements, we still count this less severe incapacity group as part of the incapacity benefits caseload after this change (and we discuss its potential effects below).”

On Chart 3.10 (which shows the WCA approval rate) they do include the ‘higher award approval rate’, which takes account of the fact that people in the less severe disability group don’t receive higher awards from April 2017 (but this isn’t discussed in the text). The conclusions also note that "the 2017 policy to reduce generosity for the less severe incapacity group is likely to have contributed to the rising share of approvals for more severe incapacity". But otherwise this issue is invisible from the charts on caseloads or on-flows (3.1, 3.3 and 3.4).

This is taken from Chart 3.5. Note that the table that is supplied for this chart is confusingly labelled (changes due to initial claims and the approval rate in 2014-15 to 2018-19 should be negative) - my text here corrects the Excel table to match the (presumably correct) interpretation in the text and chart itself.

The numbers also jump around a bit because they sometimes refer to claims in-payment, and sometimes to all claims (including credits-only claims, where people receive NI credits but no payments). As the OBR say, “on our preferred measure shown in Chart 2 [also 3.2], onflows rose by around 80,000 a year between 2010-11 and 2014-15, whereas on the broader measure shown in Chart 3 [Chart 3.5], they rose by around 110,000 over this period. Chart 3 is based on total onflows, rather than just inpayment onflows, which is why the annual onflow numbers are higher than those in Chart 2.”

Oddly, the OBR’s home page had a summary of the report that was removed later on the release day (so I now cannot see it). From memory, I think the headline was about more generous approval rates - but for some reason it seems to have been taken down. (There has been another release on the same day, but it’s strange that there’s no much of the Welfare Trends Report on the home page now, and the press release-style copy is nowhere to be found).

Even in the report, though, the emphasis is very much on the approval rate, e.g. “Onflows rose by around 110,000 a year over this period. This increase was nearly all driven by a rising approval rate, which contributed 109,000 more onflows a year. This likely reflected responses to a series of Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) independent reviews of the relatively new WCA that led to some easements of assessment criteria and to extra support being provided to claimants.” This is both technically correct, and slightly misleading.

I really appreciate that the OBR at least did mention this in the text. They say, “While instructive overall, these trends over long time periods have to be interpreted with some caution, given the different ways in which different benefits classify people over time. Most importantly, as a household benefit UC includes some partners of claimants in the incapacity benefits caseload, thereby increasing the number of individuals ‘counted’ as on the benefit relative to the predecessor ESA system." This directs the reader to a footnote which continues, “Counting individuals in a household with UC LCW or LCWRA status counts each member of the household as an individual in receipt of an incapacity benefit. ESA is paid to individual claimants so only counts individuals in receipt of ESA. This only affects caseload comparisons – there is only one LCWRA payment per household, so this does not affect comparisons of spending.” But as my blog posts make clear, this is only one of the two issues in trying to count consistently over time.

The series that I’ve created correlates with the OBR series at r=0.997 - so I’m pretty sure that this is what they’ve done, even if I’m not 100% sure.

Huge thanks Paul for some amazing comments! Mostly these can be read alongside my piece for added insight, but a couple of quick replies to each comment below

5) One thing I don't agree with is counting the ESA WRAG group (and UC equivalent) as 'unemployed' like JSA claimants and UC full worksearch. These are people who would have been eligible for Incapacity Benefit and likely Invalidity Benefit (and/or the Income Support groups required to have had the All Work Test). For consistency with previous programmes, these need to be in the analysis.

Whether they meet the ILO classification of unemployed is a different question - for the ILO, you need to have done something to look for work in a surveyed week. However, the 'something' could include what DWP would call a 'work focused interview' rather than applying for any job.